With the launch of the Nike Shox Z, one of the most radical footwear innovations of the early 21st century returns to the spotlight.

The new model is more than an evolution — it’s an invitation to revisit the ideas, courage, and mechanics that have powered Nike Shox for over four decades.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

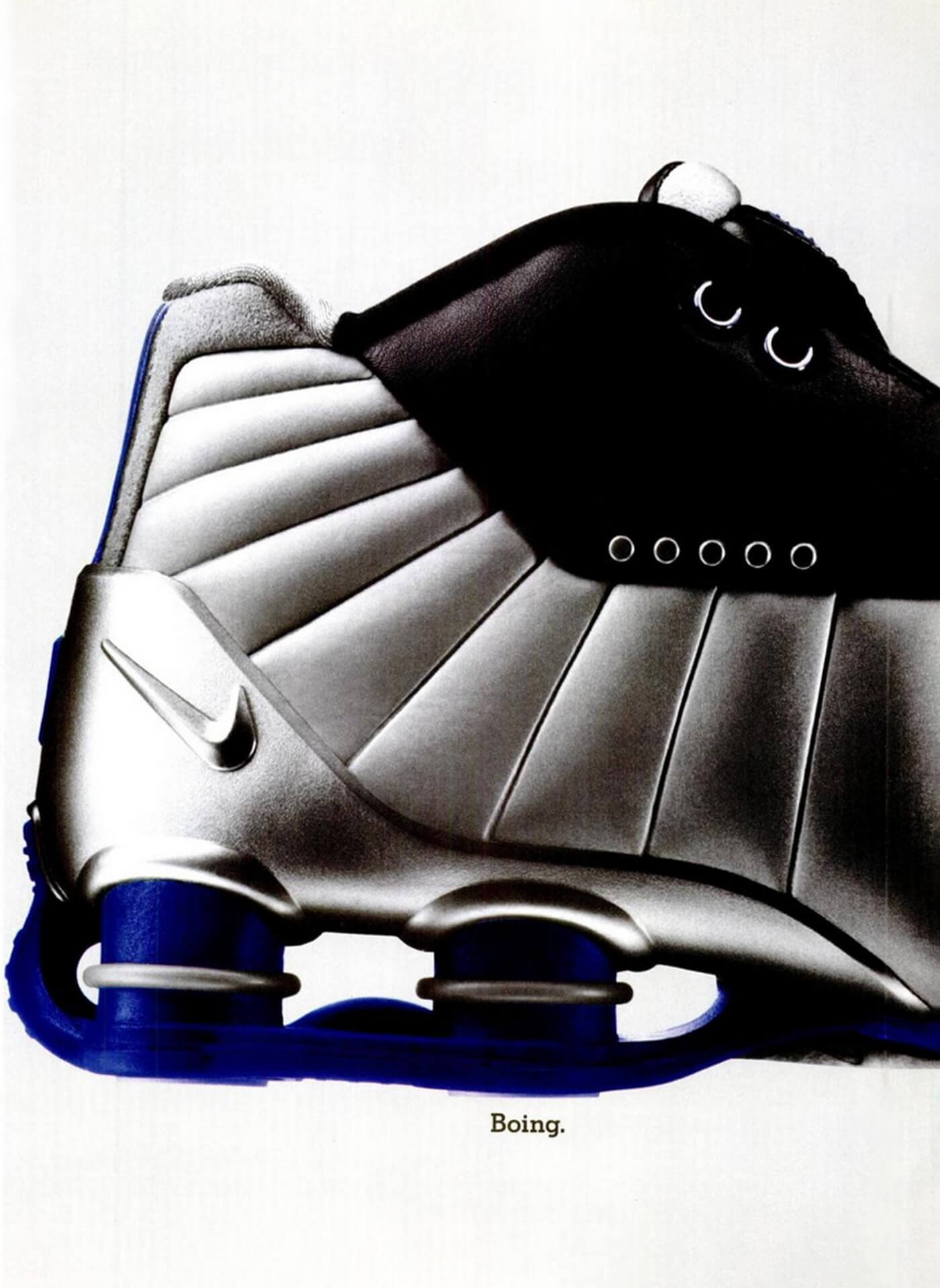

Boing.

Energy Return Before Sneakers Caught Up

The story of Nike Shox did not begin in the 2000s — itreaches back several decades. In the late 1970s, Harvard biomechanics professor Tom McMahon developed a tuned indoor surface built from layers of polyurethane and wood — engineered not just to absorb impact but to redirect it back into the runner’s stride.

Instead of losing energy into the ground, athletes experienced rebound.

It was a concept decades ahead of footwear technology.

A Brief Bounce Before Shox

Before Shox became a reality, Nike was already playing with the idea of “Boing.”

An early-1980s print ad for the Rivalry tennis model showed a sneaker balanced on two giant feathers — a playful, almost ironic image that treated “energy return” as fantasy rather than technology.

Nearly two decades later, a model called Shox Rivalry appeared — a sleek, minimal Shox design that looked strikingly similar to today’s Shox Z.

What began as a tongue-in-cheek vision became the blueprint for one of the most iconic tech ideas of the 2000s.

From Prototype Chaos to Purpose

By 1984, Nike recognized the potential and brought McMahon to Beaverton to explore how this principle could live inside a shoe.

Designer Bruce Kilgore — already known for the Air Force 1 and Air Jordan II — joined the effort. Early Shox prototypes were mechanical, messy and unstable. Kilgore described one as a “Frankenstein-looking aluminum boot.”

Engineers tested metal springs, leaf systems, hinges and cantilever-style supports. Nothing held up under stress, but the idea refused to die.

In the early 1990s, Nike turned to automotive engineering for help. The breakthrough came through high-resilience polyurethane foams used in car suspension — able to withstand immense repetitive force without collapsing. This material evolution unlocked the core of what Shox would become.

Engineering the System

Through the late ’90s, Nike refined the concept into something functional and manufacturable. Cylindrical foam columns were paired with a thermoplastic plate to stabilize rebound and prevent energy loss through the sides of the heel.

Early prototypes appeared on models like the Internationalist, Trainer SC and Air Skylon. By 1997, the technology was ready — development was no longer theoretical but directional.

Alpha Project: Innovation in Plain Sight

When Shox finally moved toward release, it did so within Nike’s Alpha Project — a late ’90s initiative dedicated to experimental performance design.

Recognizable by the five-dot logo, Alpha Project produced silhouettes like the Air Presto, the Air Kukini, the Flightposite and early Shox models such as the R4, BB4 and XT.

Designers including Eric Avar, Aaron Cooper and Bruce Kilgore treated Shox not as cushioning but as a visible mechanical system that challenged convention.

The Original Visible Tech Rebel

Before visible Air became lifestyle currency and long before foam stacks and air windows defined sneaker aesthetics, Shox made its technology impossible to ignore.

The system didn’t hide inside the midsole — it stood outside of it. Exposed columns in the heel declared function as form.

While Air put cushioning on display through windows and bubbles, Shox exposed its mechanics instead.

It wasn’t translucent. It was industrial. It didn’t ask to be understood — it demanded to be seen.

Performance, Culture and the Pivot Point

Even before fashion caught up, Shox blurred the line between athlete and aesthetic. The BB4 became a cultural marker when Vince Carter wore it at the 2000 Olympics and detonated his now-legendary dunk over Frédéric Weis.

That moment gave Nike more than a highlight — it gave Shox a mythology. From there, the silhouette moved beyond the court and into streetwear, celebrity closets and early-2000s pop culture.

It was polarizing, futuristic, heavy, mechanical and undeniably different — traits that made it stand apart long after the performance trend cycle turned elsewhere.

A System Meant to Evolve

Shox was never a side note to Air. It ran parallel to it — born from biomechanics, refined by industrial design and pushed into culture through visibility and audacity.

It was a cushioning idea decades in the making, and a fashion object years before the industry used that language.

Its return today doesn’t arrive as nostalgia — it arrives as recalibration.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Shox Z: Disruption Reintroduced

The columns are no longer just cushioning — they’re cultural architecture. What began as visible tech for athletes now returns as visible intent for everyday movement.

Shox has never stayed confined to sport, and the Shox Z reflects that. It picks up the visual impact of the original system and places it in environments where expression matters more than competition.

In that sense, Shox hasn’t come back to be remembered.

It’s come back to move differently — again.

The Nike Shox Z is available in various colorways at Asphaltgold.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Photos via Asphaltgold, Nike

.jpg)

.jpg)